Yet, when I probe more deeply into the driving questions about Montag and Mildred and government control and the power of books, he virtually leads the class discussion—books and the written word are how people stay free in the confines of a totalitarian system.

“A” references something Mr. Fusco, his history teacher, said in class, but when I ask him to bring in an article to share to explain it more deeply—double brownie points, I add, hoping for more motivation—“A” shuts down.

“A” is a real young man but represents many of the young men I’ve had over the years, young men who I have always struggled with not to pass tests or do homework, but simply to engage in the reading & writing process.

In his book Holding On To Good Ideas in a Time of Bad Ones, Thomas Newkirk types my “A” into these lines:

“These boys who have the experience of being behind, of not being good at literacy—and they number in the millions—soon turn a difficulty into an identity” (Newkirk 105).

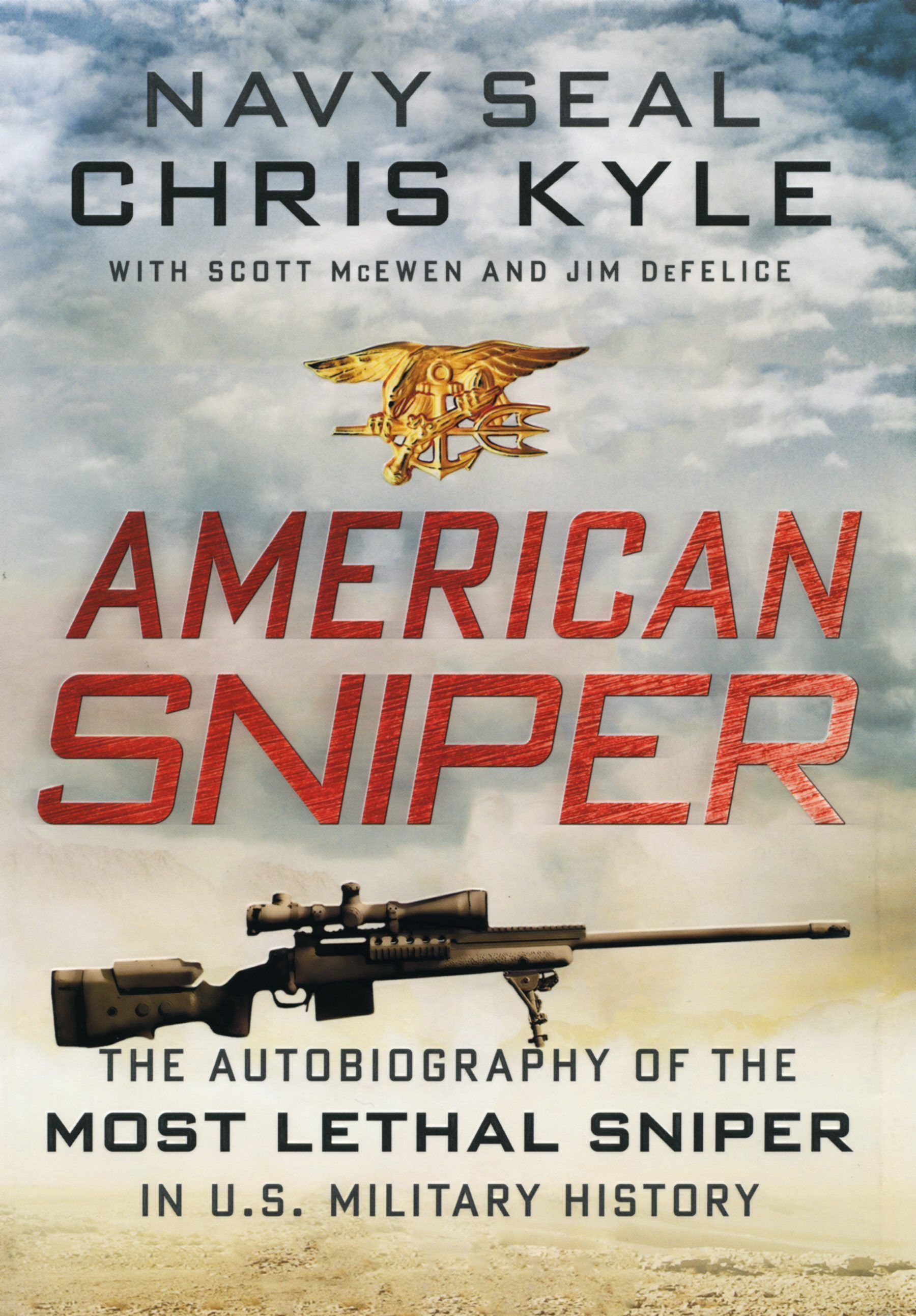

At some point throughout the years, maybe it was one day, maybe it built up, “A” started to identify himself as “not being good at literacy.” We discussed it often. He hates reading. He hates writing. For independent reading, I bought him the hard cover of Chris Kyle’s American Sniper: Autobiography of the Most Lethal Sniper “A” had been wanting to read and he took it, excited, ready to care for the new, “fresh”-in-more-than-one-way book, but he never read it. Dabbled here and there. But he never read it.

I conceived of as many ways as I could to engage “A” in more than just the incredible conversations he could maneuver. But it was difficult. Very. Until it came to our Making a Change, Taking a Stand work.

His driving question was “Why is MMA the best?” After some tweaking and important discussion about assumptions limiting the scope of research, we settled on “How is MMA superior to other sports?” The part of me that wanted to push him into something more academic surfaced and I let it go immediately. That part is ingrained in me; it’s that we-have-to-make-our-kids-do-more-rigorous-tasks voice that Charlie Brown’s teacher’s itself into our eardrums daily. But I let him do it. Why? Because it was the first time he didn’t identify himself as not good at what we were doing, because he didn’t even have time to stop and consider that he was actually reading and writing.

Maybe it wasn’t the literature of the curriculum, but he was after school every day exploring sites, seeking out reputable sources, writing his annotations, his counter arguments, his body paragraphs. He was sharing with me, with our whole class what he discovered and he loved it.

When Newkirk writes “Ultimately we don’t read to read, or write to write. We do both because of some interest in the subject—and some desire to share that interest with others” (Newkirk 141), he gets it. He gets “A” and many of the boys (and girls) that “A” represents. Because “A” had a desire to share his interest, he shed his “not good at it” attitude & embraced the voice he had to share.

Here’s his blog & something he was quite proud of. And though it isn’t polished or perfect and likely hasn’t been seen by anyone other than our class, he had a voice, he opened up to the reading and writing process.

Now that’s an idea that I’ll hold onto in this time of bad ones.